Organising

by Manfred Davidmann

Other Subjects;

Other Publications

Summary

Comprehensive review in clear language about how to arrange matters so that people can work together effectively and well. Contains much about what is needed to improve teamwork and co-operation, particularly in large organisations where many experts have to work together in teams.

Discusses the role and responsibilities of managers in different circumstances. Also discussed are relationships between people at different levels and relationships between people and groups.

Outstanding is the section on functional relationships and that on co-ordination and co-ordinators, based on much experience and fieldwork.

This report is a comprehensive guide to ways of finding basic causes of such problems and shows how to solve them.

Contents

Community Leadership and Management:

ORGANISING

- Organising

- Organisation Charts

- Division of Work

- Work Done (Responsibility Carried) at Different Levels

- Relationships Between People at Different Levels

- Co-ordinating Work Between People

- Behaviour Between Managers and Subordinates

- Behaviour Between Managers and Work Groups

- Functional Organisation

- Requirements and Definitions

- Organising for Teamwork

- Role of Manager

- Disorganisation and Co-ordination

- (Effect of management style on way people work together in large organisations, that is on the effectiveness of large organisations)

- Role of Manager

- Notes <..> and References {..}

- Illustrations (Click any illustration to see the full-size chart)

- 1 Organisation Charts

- 2 Organisation Chart

- 3 Dividing the Work

- 4 Work Flow Diagram

- 5 Project Organisation

- 6 Project or Matrix System

Relevant Current and Associated Works

Relevant Subject Index Pages and Site Overview

ORGANISING

We have already looked at the work of those who lead and direct, from the point of view of deciding policy and setting targets in the light of modern quickly changing conditions {1}. In other words, we know what has to be achieved.

However, what an organisation has to achieve requires work to be done in many different areas, requires much knowledge and experience which is often highly specialised. Hence the work is divided among work units such as divisions, departments and groups. The work requiring to be done by the community is similarly divided into different areas such as industrial, educational, social, welfare, civil security and so on.

We also looked in considerable depth into the effect which the style of management has on people, on the way in which people work together and on the resulting effectiveness {2} of the organisation. Large organisations require many experts to work together and for the work to be done effectively and well, indeed for large organisations to succeed in doing their work without endangering the community, requires people to work together and to co-operate with each other, requires a participative style of management.

We also saw that in a participative setting the work of the manager is very different from that in an authoritarian organisation. It is easier but much less effective to be given orders and to pass them on by way of instructions when comparing this with the much more difficult and indeed much tougher job of the manager in a participative organisation.

Hence what we are discussing here is how to arrange matters so that people can work together to get the work done, looking at the division of work between people and groups, at the work done by managers at different levels, and at co-ordinating the work of people and groups to enable aims and objectives to be achieved.

ORGANISATION CHARTS

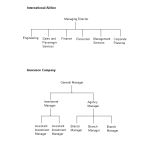

| Figure 1 Organisation Charts |

|

Organisation charts, a form of line diagram, show work units in relation to each other. Titles of managers are given, as are names of work units and of their managers. Such charts indicate the arrangement of work units and the delegation of work, that is the delegation of responsibility. They vary in scope and detail from those showing the organisation of related institutions or companies to those showing the detailed organisation of a small work unit.

Some organisation charts are shown in Figure 1. It is seen that levels of position indicate the manager/subordinate relationship between individuals, indicate the reporting chain. Names and/or titles can be given as well as explanatory notes so as to clearly show who does what and who reports to whom.

In general, a person is responsible to his immediate manager for his own work and for that of his subordinates, and this is shown by the lines on the chart. Hence the organisation chart is used to illustrate:

- The division of the company's work into work units (who does what); and

- the reporting chain (who reports to whom).

The organisation chart is an extremely important tool for analysing problems in organisation and this means for analysing day-to-day problems of management.

| Figure 2 Organisation Chart |

|

But every tool can be misused and far too often do we see organisation charts which show diagonal lines between different reporting chains, which attempt to show much else. Immediately the organisation chart is used to show relationships between people in different groups such as departments, it fails in its function, becomes confused and misleading.

It is equally important to remember that there is no other significance in the relative position of one person compared with another. Figure 2 illustrates this point. This organisation chart shows 'B' and 'C' both reporting to 'A'. This does not mean that 'B' and 'C' are at the same level of seniority or status within the organisation. For example, 'B' may be the Works Manager and 'C' may be the head of the typing pool.

The use of organisation charts for analysing organisational problems of management can now be illustrated by examples. These deal with problems resulting from the way the work is divided among work units and from reporting, that is from relationships between managers and subordinates.

DIVISION OF WORK

The work is divided among work units such as companies, divisions, departments or groups. Each work unit's manager is responsible for the work done by his unit as well as for the work he does himself.

But now let us look at some common and basic problems which can be tackled by means of an organisation chart bearing in mind that people are often deeply involved and feel strongly about situations such as these in which they are directly involved.

| Figure 3 Dividing the Work |

|

Consider the work for which the departmental head 'A' is responsible (see Figure 2). He has divided it among his managers 'B' and 'C'. This is shown in Figure 3a which illustrates that the work done by 'A' has been divided by him among 'B' and 'C' as shown and all is well.

But let us assume that he divided it differently, say as illustrated in Figure 3b. There is a gap. Some work that requires to be done has not been allocated and 'A' is not aware of this. This means that in due course some crisis arises when this becomes apparent. 'B' or 'C' could have assumed that it was the other who was dealing with the matter or that 'A' was doing the work himself, or that it was being done in another department. Another possibility is that 'B', having realised that it was not being done, took it upon himself in a particular case to do the necessary work. This may upset another colleague who feels that he should have been doing it in the first place. For that matter it may not be done very well because 'B' is not particularly skilled in this type of work. Or, having done it once, 'B' may continue to do this kind of work in the future and so come in conflict with other colleagues who would also like to take over what may be an interesting part of the work.

On the other hand the work could have been allocated as shown in Figure 3c and this now raises some additional interesting possibilities. There is an overlap. 'B' and 'C' are now responsible for, are now supposed to be doing, the same work. It could be done twice, by 'B' and by 'C'. If they both got the same answer and did the same thing, this might not be important. However, a problem does arise if they get different answers and do different things. Much more serious would be that 'B' could assume that 'C' was doing it and 'C' could assume that 'B' was doing it. So on the one hand the work could be done twice, but on the other hand it could be forgotten altogether.

The point which is being made here is that in this way the organisation chart can be used at different levels to look at the work done by different people in different groups so as to sort out problems which show up as crisis situations. We have seen it applied to problems of work having been done twice and of work not getting done, and to problems which arise between different groups about the division of work, about who should be doing what.

WORK DONE (RESPONSIBILITY CARRIED) AT DIFFERENT LEVELS

It goes almost without saying that the work differs at different levels of management. Yet there are a considerable number of people, particularly managers, who continually maintain that they could do their own manager's job better than he can himself.

This may indeed be so in isolated instances, but in my experience it often arises from a lack of understanding of the difference between the work being done by the individual compared with that being done by that individual's manager. Indeed, it is almost from the moment that the individual becomes aware of the difficulties his manager is facing and appreciates some of the problems of the manager's job, that he is beginning to work at the higher level, that he is beginning to prepare himself and train himself for working at the manager's level.

Consider an engineer's progress. He may indeed start with a university degree but has little practical experience and spends some years in designing installations and perhaps also in commissioning them in the field, handing them over in satisfactory working order to the client. His practical experience reinforces the design knowledge he has gained, he gets to know the way his company works, that it is important to serve the customer just as it is important to deliver the goods on time and not to exceed cost estimates.

He can now work at the higher level, becomes a senior engineer and has two or three graduates assisting him with the work that he is now doing. He does much the same as before but instead of dealing with single plant items he now deals with rather larger installations. His responsibility is now greater, not just because the contracts are worth more but also because to some extent the way in which his team works depends on him. However he is unlikely to make personnel decisions or indeed policy decisions about engineering matters.

In due course he may indeed be promoted and become a departmental head. Now he may negotiate with important clients, make policy decisions about engineering methods and safety factors, is very much concerned with the organisation of the department and with the way in which the department works with other groups.

Engineer becomes senior engineer who in turn becomes departmental head. As he moves from level to level so the engineering content of the work becomes less. The managerial content which is the management of people and resources becomes much more important, occupies more time, determines performance.

If he becomes a director of the company then again the work changes. He is now concerned with giving expert advice to the board on engineering matters but also participates in thinking ahead, in guiding the organisation, in setting its direction and speed. He is now beginning to get more involved in directing the organisation in addition to the managerial work he is already doing.

I could have mentioned earlier the difference between working on the shop floor, supervising and becoming a foreman. There is here again a similar change in work content dependent on the level although the actual work and work content is different from that which I have described for managerial levels.

Those who wish to move from one level to the next need to be aware of the different problems at the next higher level and equip themselves either through experience or background study for that work.

However, we need to be aware that we are here considering different levels of management within the organisation, that we are talking about the work of the manager only in relation to his job.

RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN PEOPLE AT DIFFERENT LEVELS (LINE RELATIONSHIPS)

The organisation chart enables one to consider the relationships between a person's manager and his subordinates in a very clear and effective way. Let us consider some of the do's and do-not's of these line relationships in the reporting chain.

Let us look again at the organisation illustrated by Figure 2. It shows the organisation of a small department consisting of the departmental head, two managers and five assistants. The organisation chart shows who reports to whom.

One day the departmental head 'A' meets assistant 'H' in the corridor, asks him to get some work done and hands him the necessary papers. Assistant 'H' is delighted with this. He feels that his true worth is at last being recognised. The departmental head himself is giving him work to do! He immediately goes to his office to get the work done, to get it back to 'A' as soon as possible. He produces a first-class job and gets it to 'A' very quickly indeed and 'A' is, of course, delighted. He gets the impression that 'H' is doing very well, is obviously a good chap indeed.

It so happens that shortly after 'H' returns to his office, highly pleased with himself, that his manager 'C' asks about some work that should have been completed some time ago. 'H' points out that he could not do it because he has been doing work for 'A' himself.

Put yourself in the manager's position. How would you feel about this kind of a reply from someone who is working for you? Not only is manager 'C' upset because he has been bypassed, but looking at this objectively it becomes clear that manager 'C' cannot do his job under such conditions. He has to allocate and co-ordinate the work done by the team he leads. When others such as 'A' bypass his arrangements this makes it difficult if not impossible for him to do his job properly.

It is not just 'C' who has been upset. In due course assistant 'H' feels the strain as he is working for two people, is responsible to two individuals.

Consider the position in which assistant 'H' finds himself just after he has been given work by the departmental head. What can he do? One alternative would be to take the work he has just been given to his manager and mention that he is doing some work already for him which is urgent and ask him to decide priorities. The assistant is in this way backing his manager and is maintaining the effectiveness of the unit, but would in that case be doing what 'A' should have done, would be working at the level of the departmental head. If you by any chance have an assistant who is backing you in this way then you can consider yourself lucky since he is acting at a high level of managerial understanding and responsibility.

Put in another way {3}, the lines of Figure 2 reveal that assistant 'G' does not report to departmental head 'A', either directly or through manager 'B', as this would mean that he is bypassing his immediate manager 'C'. Such bypassing would mean that manager 'C' could not effectively control the work done by his subordinates and it would antagonise him. It would in due course upset the subordinate as well, as he would appear to be working for two managers, with resultant uncertainty of position. In other words, bypassing upsets the organisation, the bypassed executive being unable to effectively carry out or have carried out the work for which he is responsible.

CO-ORDINATING WORK BETWEEN PEOPLE

Extending this argument to people working at the same level, it is seen that they each report to their own immediate manager, doing so only on matters for which they are responsible, on work done by themselves or their subordinates. For example, manager 'B' reports to departmental head 'A' only on work for which 'B' and his assistants 'D' and 'E' are responsible. He does not report to 'A' on work done by manager 'C' and by C's team and he should not be asked to make such a report.

If he were asked to make such a report then two executives at the same level would in effect be responsible for similar and overlapping work <1>, and immediate conflict between the two executives can result, to the detriment of work done by either one or the other or both. Divided responsibility would mean that two work units could be duplicating each other's work, or that some work might not be done at all since each work unit assumes that it is being done by the other. It is possible when responsibilities are badly defined that neither would benefit from results obtained in the field.

The organisation chart (Figure 2) shows that if 'B' were to report to 'A' on work done by 'C', then 'B' would in effect be placing himself between 'C' and 'A'. This is generally much disliked by the manager in C's position.

Suppose 'D' is waiting for an estimate to be completed by 'E' before he (namely 'D') can send out a quotation. The quotation has to be posted within two days and it looks as if 'E' will be unable to provide the information in time. 'D' could write to 'E', with a copy to their common manager 'B' and point out that unless the estimate is received by a certain time on a certain day then his quotation would be delayed and that the chance of getting this order would then probably be lost.

He has not complained to manager 'B' about lack of service from 'E'. He has pointed out to 'E' the urgency of the position and the consequences of delay, leaving it to 'E' to discuss with manager 'B' his (that is E's) priorities, being fully aware of the circumstances.

The same applies between 'D' and 'F'. Here 'D' could write to 'F' with a copy to 'B'. It would be up to 'F' to sort out priorities with his own manager 'C' and it would be up to manager 'B' to take this up, if he thinks it necessary, with his colleague 'C'. In the end 'B' might well write to 'C' with a copy to 'A'.

In other words {3} the organisation chart shows the division of work and the reporting chain, and if this is bypassed, or if responsibility (that is work) is divided so that one person is responsible (that is accountable) to two managers, or if work is divided so that two executives are responsible for overlapping work, trouble can be expected.

BEHAVIOUR BETWEEN MANAGERS AND SUBORDINATES

Locating Basic Causes

Far too often do we find that managers spend their time happily making decisions, dealing with emergencies and getting a great deal of satisfaction from resolving such situations with the decisions they make. However, one emergency succeeds another and they do not realise that they are running as fast as they can merely to be standing still.

The reason is that there are symptoms and causes, that the emergency has its cause. The manager's decision deals with the immediate situation but does not as a rule resolve the basic cause which continues to produce more problems requiring further decisions to resolve them. Hence the manager needs also to go beyond the immediate situation, needs to diagnose and locate its basic cause. Once this has been done it can be dealt with.

The organisation chart is a very useful aid which enables one to think objectively and systematically about basic causes and to illustrate them.

Work Flow Compared with Work Allocation and Responsibility

I remember talking to a manager at the assistant level about the disadvantages of bypassing, when he said: "I am in H's position (see Figure 2) and I get work from 'A'. I also get work from 'C' and indeed some work reaches me directly. I do the work and the system works very well." This appeared to contradict what I had been saying.

He was responsible for receiving regular reports from different branches in the UK and abroad, for carrying out some calculations, for entering the result of his calculations on the reports and for then passing them on.

Some reports reached him directly from 'A' and after recording the result of his calculations on the reports he returned them directly to 'A'.

Other reports were sent to him by most of the branches, and he again entered the results of his calculations and sent them back to the branches.

But reports from a few specified branches were sent directly to his manager 'C' who made such comments as he thought necessary and then passed them on to 'H' who again entered the results of his own calculations. But these he sent back to his manager who had to approve what had been done before the reports were returned to the branches.

'H' was right, it had worked extremely well.

The work done for 'A' was important. It had to be done fairly quickly but the work was routine and manager 'C' had asked assistant 'H' to deal with it directly and was confident that 'H' would do this work well and could be relied on to do so without supervision. It was manager 'C' who had arranged for the work to flow directly from 'A' to 'H' and to be returned by 'H' to 'A'.

The same applied to work for most of the branches and manager 'C' had arranged similarly for the work to reach assistant 'H' directly and for it to be returned directly by 'H' to the originating branches. Manager 'C' was confident that assistant 'H' would contact him should any problem arise.

The reports from a few of the branches were sensitive, meaning that there were reasons for manager 'C' wishing to have a close look at their reports both when they came in and before they were returned to the branches. Hence he arranged to see these returns before passing them to 'H' and to see the completed reports before they were sent out.

These are work flow arrangements, arranged by assistant 'H' together with his manager 'C'. These arrangements in no way affected manager C's responsibility for work being done by 'H'. What he had done was to arrange the flow of work in the best and most effective way for getting the work done.

There was here no question of bypassing since what we were looking at was work flow and not responsibility or reporting. The manager had delegated the work so that it was done at the lowest possible level, had passed on the greatest possible amount of responsibility, had done his work well and as a result the whole system of work flow worked very well indeed.

The point made here is that work flow on the one hand and the allocation of work and responsibility on the other, are two quite different matters. The organisation chart shows the division (allocation) of work and responsibility and the reporting chain. Work flow systems are a different matter and do not necessarily correspond to lines on an organisation chart.

In another case one manager said that he was responsible to three senior managers and he insisted that this was so. When asked: "To whom are you responsible? Who assesses the quality of your work? Who appraises you? Who decides what increase you get at the end of the year?" he could only say that he was responsible to three managers.

| Figure 4 Work Flow Diagram |

|

Figure 4 illustrates this point. It could well happen that one manager receives work from three other managers, does whatever he has to do and then returns work to them, as illustrated by Figure 4a. This does not mean that he is responsible to three managers. If one man were responsible to three managers the organisation chart would look like that illustrated in Figure 4b. It simply does not make sense and this sketch enabled the company to clear up the confusion.

The allocation of work and responsibility and consequent reporting are quite different from work flow and one should be careful not to confuse one with the other.

BEHAVIOUR BETWEEN EMPLOYEES AND WORK GROUPS

We have talked about the division of work from the point of view of allocating all the work so that there should be no gaps and no overlaps. But the work needs also to be divided so that each group is doing a particular kind of work in which they have and develop expertise and where experience and results may be accumulated and used to improve the level of working and the work which is being done.

This means that division of work has to be functional and it implies that one looks carefully at the work done by different groups and departments and considers them side by side.

An organisation chart may emphasize which are the front-line departments at that particular point of time, which are supporting, which provide a service and which, if any, serve head office and the board. Front-line may be production or it may be selling and marketing, supporting may be the engineering division. Service divisions could be finance and personnel, while head office and the board may be backed by a corporate planning department.

In an insurance company it may be selling or it may indeed be the successful investment of its funds which determines company results.

In telecommunications it could be either selling of equipment or else operating the telecommunications network which is regarded as the main business of the company, or indeed both together, side by side, dependent on conditions existing at the time.

In engineering contracting it could be selling, designing, procurement or construction which are regarded as front-line divisions, although of course all four need to co-operate and each one needs to do its work according to plan and within cost estimates so that the completed contract can be handed over to the client on the promised day, within the cost estimate, working to the client's satisfaction.

Misunderstandings between employees or groups concerning the division of work, work allocation and priorities in the end need to be resolved at that position on the organisation chart where the two lines meet. Here lies the responsibility for effective organisation, for sorting out such problems.

The sorting out of problems such as these would take place in the first instance by talking with people, by discussion. Different organisations have different practices dependent on the style of management, dependent on the trust, co-operation and teamwork between those who work in them but almost invariably the resulting decision is confirmed in writing.

Many difficulties arise from the way in which people work together in different groups or departments and it is because of this that large organisations generally fail to achieve the kind of close co-operation so common in smaller companies.

FUNCTIONAL ORGANISATION {9}

REQUIREMENTS AND DEFINITIONS

To ensure effective teamwork between work units, the division of work between them has to be clearly stated and functional relationships have to be defined.

In an effective organisation each work unit has to be responsible for, and carry out, a separate specialist function essential to the carrying out of the organisation's task. In the case of a chemical plant contractor, for example, the organisation's task is to provide chemical plants and this task may be subdivided functionally into 'direct' and 'indirect' work tasks.

A direct work task is one which is directly concerned with the carrying out of the work of the organisation as a whole. Examples are the designing of a plant for a customer, or research into new processes so as to extend the range of plants offered to customers.

The executive responsible for carrying out a direct work task is the 'responsible' executive.

An indirect work task is one which is indirectly concerned with the work of the organisation as a whole. Examples are the work done by a personnel department or that done by an executive in one work unit who is providing a specialist service for the 'responsible' executive in another work unit.

The executive responsible for carrying out an indirect work task acts as specialist adviser; that is, he is the 'prescribing' executive.

Relationships between executives in different work units are functional relationships. Of the two executives concerned, one is 'responsible', the other 'prescribes'. The responsible executive is fully responsible to his executive superior alone for obtaining specialist advice, for accepting or rejecting this, and for reporting useful results back to the prescribing executive. The prescribing executive is fully responsible to his executive superior alone for giving specialist advice and for the quality of his prescription.

The same executive may be responsible for the carrying out of both direct and indirect work tasks. Where this is not clearly seen, and when the difference between the two types of tasks is not understood, then difficulties may be expected. It is important, therefore, that the type of task be clearly realised, in each case, by the executive who is carrying it out.

ORGANISING FOR TEAMWORK

Design and Research in Chemical Plant Contracting

To ensure effective teamwork between Research Department and Chemical Plant Design Group, their responsibilities, and the functional relationships between them, can be defined as follows:

Chemical Plant Design Group

The Head of the Chemical Plant Design Group is entitled Chief Chemical Engineer. He is responsible for chemical engineering design and development, for commissioning and proving, for satisfactory performance and operation of the chemical plants designed by chemical engineers working in this group. By development is meant the comparing of actual with predicted results and the correlating of the conclusions so as to improve the quality of the group's work. All chemical engineering design work that requires to be done within the organisation is carried out by chemical engineers working in this group. Their work consists of both direct and indirect work tasks. Their direct tasks consist of chemical engineering work on plants for customers; their indirect tasks consist of carrying out similar work for the organisation's other work units.

While carrying out a direct work task, the chemical engineer is the responsible executive. While carrying out an indirect work task he is the prescribing executive.

Research Department

The head of the Research Department is entitled Research Manager. He is responsible for effectively searching for new processes. All research work that requires to be done within the organisation is carried out by scientists working in this department. Their work consists of both direct and indirect work tasks. Their direct tasks consist of searching for, and evaluating, new processes. Their indirect tasks consist of carrying out research work for the organisation's other work units.

While carrying out a direct work task, the scientist is the responsible executive. While carrying out an indirect work task, he is the prescribing executive.

We have defined here the division of work and the functional relationships between two work units, but not the complete activity of either, being concerned only with that part of each work unit's activity which may affect the relations between them.

ROLE OF MANAGER

DISORGANISATION AND CO-ORDINATION

Here we are looking at the effect of the style and quality of management on the way in which people work together in large organisations, that is on the effectiveness of large organisations.

In large organisations many experts have to work together and problems are encountered as a result. In chemical plant contracting the many problems which can be encountered in managing large organisations are present to a very marked degree. The installations being installed are large and include complete oil refineries and nuclear power stations. They result from the joint work of many experts who need to work together as an effective team if the project is to be successful, meaning by this if it is to be completed within cost estimates and if it is to be commissioned and handed over to the client by the promised date working to the client's satisfaction. At the same time one is dealing with advanced levels of technology particularly when it comes to satellite propelling and launching installations and with computerised automation and control.

Difficulties have of course been experienced in obtaining effective teamwork and as a result the chemical plant contractor tends to allocate the work to project teams. The project engineer, in charge of the team, is responsible for the project. Further difficulties then arise when a number of projects are being handled at the same time, particularly when the contractor is working at top capacity, quoting short delivery periods in a competitive market.

Many experts have to work together and their work is inter-dependent. There are process design engineers, instrument engineers, electrical engineers, mechanical engineers, civil engineers, estimators, buyers, accountants, erection engineers, production engineers, sales engineers, designers and draughtsmen and still others.

What happens between them, the difficulties which may arise and what the company may do as a result has already been discussed in considerable detail {3}. One man may make a decision which should be made by a colleague in another group. Some work may not get done at all as it is assumed it will be done by someone else. A change which is made at a later stage in one department may be well advanced before those in other groups or departments realise that it involves them in corresponding changes. Hence work is delayed and costs are increased.

The organisation of the company is not clear to those who work in it. Employees are not aware of where their work starts and where it finishes, where someone else takes over. They are not aware of the extent of their own responsibilities in day-to-day contacts with colleagues, customers, suppliers or sub-contractors. They are not aware of the kind of decisions they may make, of the kind of decisions that need to be made by other people working in other departments.

One way of overcoming the situation appears to be to give specific individuals the task of 'co-ordinating' work done by different individuals in other groups and departments. For example, it may be laid down that only Buying Department may contact outside suppliers and sub-contractors and that all correspondence from within the organisation must be through a nominated buyer in the Buying Department.

On the surface this seems a simple arrangement as Buying Department has full control over contacts with outside suppliers and over internal contacts regarding supplies from the company's own works. However, Buying Department now acts as a forwarding agency and is concerned with matters not directly related to purchasing. A large amount of inter-departmental correspondence is unavoidable and a considerable amount of time is now spent by Buying Department staff in arranging and taking part in technical discussions.

The Buying Department is now checking and at times 'correcting' work done by those within the organisation who come in contact with outside suppliers and sub-contractors and sometimes even the work of those who need to contact one's own factory.

One needs only to look at the number of engineers who have to work together to design just one installation, to see the kind of difficulties that could arise when a number of installations are being dealt with at the same time. A considerable overlap is likely and some work may not be done at all. Work done by one group can run contrary to the requirements of another.

| Figure 5 Project Organisation |

|

What is often done is to appoint a new kind of executive who is called a project engineer. His job is to 'co-ordinate' the work of different kinds of engineers who work in different design groups. This appears to be a more effective arrangement but direct contact between the design groups is soon frowned upon and the project group acts as a post office. The project engineer now assumes responsibility for design. As a number of plants are being designed at the same time, a designer now has his responsibilities divided among his own immediate superior and most likely two or more project engineers as can be seen from Figure 5 'Project Organisation'.

In due course project engineers add other aspects of the company's work, such as purchasing and construction, to the activities they co-ordinate.

What has happened can be described as follows:

- The way people, groups and departments work together leads to difficulties, individuals in different groups not working together effectively.

- This is realised and a solution is attempted along the lines of checking the work done by the various groups or departments. 'Co-ordinators' are appointed because it is realised that there are internal defects in organisation, that people do not co-operate as well as they should.

- This generally makes the organisation more cumbersome, creating more paperwork. Where two people worked together before, there now stands between them a third, the co-ordinator.

- The 'co-ordinator' relies on the co-operation of those whose work he checks. If they did not work in harmony before his arrival, they are scarcely likely to work well subsequently, especially since his position and work appear vague. Hence he asks for the authority to command co-operation. He cannot be given authority without responsibility and thus he is given responsibility for at least some functions.

- This immediately cuts across the functional division of the organisation, that is across established chains of responsibility and reporting, bringing in its wake divided responsibility and going some way towards breaking up specialist departments as illustrated by Figure 5. The organisation loses efficiency, becomes even less effective.

- To meet the situation, the 'co-ordinator' may be given still more responsibility, reducing the organisation's effectiveness still further.

In the end functional departments in effect disappear altogether and are replaced by teams, each being a small contracting organisation of its own as shown by Figure 6 'Project or Matrix System'. Each team at this stage is likely to repeat all the mistakes made already by other teams. Project teams take precedence over functional groups and specialists have difficulty in keeping abreast of their subject as know-how tends to be scattered in project files instead of being absorbed and correlated by the specialist's own group. At this stage the company fails to learn from past mistakes. The same mistakes continue to be made, the same sort of difficulties keep on arising.

The appearance of a cross-group or cross-departmental 'co-ordinator' within an organisation signals that specialist groups and departments do not work well together. He has a vested interest in keeping people apart who should be working together. His appointment is no solution and makes the situation worse.

Figure 5 shows what can happen to an organisation (Figure 2) when 'co-ordinators' are appointed and shows the resulting confusion which arises. Just what is the work done by such co-ordinators?

Co-ordinator PE.1 co-ordinates the work of E and F. Co-ordinator PE.2 co-ordinates the work of D, F and H.

The co-ordinators were appointed because employees did not work well together. It is C's responsibility to co-ordinate the work of F and H by allocating work and by deciding priorities but now PE.2 is co-ordinating some of their work. Similarly it is A's responsibility to co-ordinate the work of B's and C's groups but now PE.1 and PE.2 are doing at least some of this work. The existing management has apparently fallen down on the managerial aspects of its work, have failed to get effective teamwork and outsiders have been brought in to do it for them and are taking over those aspects of their work which are concerned with managing.

Heads of functional divisions, departments and groups have lost some of their responsibilities and authority to co-ordinators, to administrators. This is naturally resented by them and their staff and creates frustration and discord. People are now much more confused about who is responsible for work allocation and for deciding priorities particularly when like 'F' they are responsible at the same time to more than one project engineer and to their group's manager.

| Figure 6 Project or Matrix System |

|

As the co-ordinators get more responsibility the organisation becomes that illustrated by Figure 6. It is called a project system in engineering contracting but called 'matrix' or 'task force' system elsewhere. Co-ordinators allocate work and decide priorities. A close look at Figure 6 not only shows the divided responsibility and resulting confusion but that the co-ordinators (project engineers or administrators) have taken over the managerial work content of the managers of the line, specialist, supporting and service groups and departments, have in this way reduced and taken over the better paid part of their work and their promotion prospects. The system is based on divided responsibility. It cannot and does not work even adequately.

One cannot expect people in such organisations or those outside to appreciate the causes of such problems but the effects soon show and in the end become obvious.

The effects and their cost, and thus the savings which can be achieved by effective organisation, that is by effective leadership and teamwork, are illustrated by the delayed completion and additional costs of large engineering installations.

Here are a few examples {4}:

| Contract | Number of Years Behind Schedule | Likely Additional Cost (£) | |||

| 500,000 tonnes ethylene plant for ICI - British Petroleum. | 1 year | £ 30 million | |||

| Chemicals complex for Monsanto at Seal Sands, Teeside. | 1 year | ||||

| Ekofisk Field terminal for Phillips Group, also at Seal Sands. | 3 years | £ 300 million | |||

| Central Electricity Generating Board's power stations building programme. | |||||

| Ince "B" on Merseyside. | 3 years | ||||

| Dungeness "B" in Kent. | l0 years | £ 255 million | |||

| All 7 stations being built. | £ 900 million | ||||

The working atmosphere in the whole organisation can change dramatically following the introduction of a 'matrix' system of administration (Figure 6).

This happened to a well-known British academic institution. Enthusiasm, academic excellence and reputation were replaced within a period of about two years by declining standards of work, frustration and lack of interest and involvement. The number of administrators increased drastically, procedures became more formal and far more involved and cumbersome. The dissatisfaction of the academic staff with their working conditions and their working environment was unavoidably transmitted to its own students and the institution's reputation among students as a whole was quickly impaired.

Britain's National Health Service was reorganised in l974. Four years later its deteriorating effectiveness was common knowledge.

There were about 2,600 national health service hospitals and the service spent about £6,000 million each year. It was largely those who worked in the service who pointed out {5} that:

- A deluge of instructions, guidance and advice came from the centre, often without appreciation of the practical implications.

- The national health service had travelled a long way along the road to declining standards and that

- morale in the service was low. Disputes and stoppages had increased alarmingly during the previous two or three years. Internal conflict and confrontation increased in severity and disputes became more bitter.

- There was increasing support for more decision making, and control of resources, by authorities nearest to the point where services are provided for the patient.

- There was increasing demand for all regional and area authorities to learn better ways of organising.

What we have seen are the disastrous consequences which happen as a result of inadequate management, that is as the result of greater centralisation, of more authoritarian management and as the result of introducing a separate 'co-ordinating' or administrative set up with consequent divided responsibility and increased centralisation.

It is because of this that it is so very important that those who head organisations understand the basic do's and do-not's of organisation, understand the role and work of managers. On the one hand those who head organisations may be getting bad advice but on the other it is up to them to accept or reject the advice they are given. It is they who determine the way in which people work together in their organisations and the following section on the role of managers summarises some of our findings as an aid towards avoiding pitfalls and as a guide towards obtaining effective teamwork.

ROLE OF MANAGERS

We saw {2} that it is relatively easy to be given an order and to pass it down by way of instructions in an authoritarian setting as one avoids the making of decisions and the carrying of responsibility. But this is inefficient and ineffective no matter which way you look at it.

Much tougher and challenging but also much more effective and rewarding is the job of the manager in a participative organisation and this applies to both small and large organisations.

Large organisations require many experts to work together. They have to co-operate with each other if they are to succeed in doing their work effectively and well without endangering the community. In other words, large organisations require a participative style of management.

Basic is that the manager needs to understand that there is participation in decision making at all levels since those who do the work are responsible for the way in which they do it and that it is work (responsibility) which is delegated so that the work gets done at the lowest level at which it can be done. Important is the basic requirement that it is he, the manager, who has to clear difficulties out of the path of his subordinates.

He has to co-ordinate the work being done by the members of the team he leads and co-ordinate their work with that of the team at the next higher level in which he is a team member.

He has to look at work done by people working at different lower levels and at the division of work between people and groups, so as to organise and co-ordinate their work to enable targets to be achieved and so as to ensure effective co-operation and teamwork.

The manager needs to understand that people in a participative organisation seek to work at a higher level, that is seek greater responsibility, so as to develop their responsibilities to the full, so as to work at the highest level of which they are capable, so as to derive the maximum of both satisfaction and reward. He needs to be aware of the factors and the kind of behaviour on his part which will create a working environment in which work will be a source of satisfaction to those who work in it so that it is performed voluntarily, willingly and well. {6}

He needs to know that people need to be rewarded according to the work they do and will help them to develop their capability, help them to work up to a higher level so that they can be better rewarded. {7}

The damage done by those who are not up to the demands of the job, by those who were inadequately prepared or trained for this work, is virtually unimaginable.

We see that the work of the manager in a participative setting is both tough and challenging. It is very much worth while for the necessary skills to be developed in managers, not only from the point of view of those who work in the organisation but from the point of view of the organisation as a whole. For example, we know that productivity can be increased by between 20 and 25% as a result of introducing a more participative environment, as a result of managers developing the appropriate skills. <2>

The higher up the manager works, the more important it is that he should be aware of the required skills and of the need to encourage others to develop and apply them, and of the reward to be gained by doing so.

The importance of the role of the manager is underlined by the need to create a participative working environment and to manage in a way which serves not only the owners of the organisation or those who control it but also the employees, the community in which his unit operates and the organisation's customers or clients. {8}

NOTES AND REFERENCES

NOTES

| <1> See 'Division of Work'. | ||

| <2> In {2}, see 'Training'. |

REFERENCES

| {1} | Directing and Managing Change Includes: Adapting to Change, Deciding What Needs to be Done; Planning Ahead, Getting Results, Evaluating Progress; Appraisal Interviews and Target-setting Meetings. https://www.solhaam.org/ Manfred Davidmann |

|

| {2} |

Style of Management and Leadership https://www.solhaam.org/ Manfred Davidmann |

|

| {3} | Solving Problems in Organising

Chemical Plant Projects, Manfred Davidmann, Social Organisation Ltd |

|

| {4} | Times, 21/8/78 | |

| {5} | Times, 15/8/78 | |

| {6} |

The Will to Work: Remuneration, Job

Satisfaction and Motivation https://www.solhaam.org/ Manfred Davidmann |

|

| {7} |

Work and Pay; Incomes and

Differentials https://www.solhaam.org/ Manfred Davidmann |

|

| {8} |

Social Responsibility, Profits and Social

Accountability https://www.solhaam.org/ Manfred Davidmann |

|

| {9} | Management Teamwork: Design,

Development and Research Manfred Davidmann, Social Organisation Ltd |

Relevant Current and Associated Works

| A list of other relevant current and associated reports by Manfred Davidmann on leadership and management. | ||

| Title | Description | |

| Style of Management and Leadership | Major review and analysis of the style of management and its effect on management effectiveness, decision taking and standard of living. Measures of style of management and government. Overcoming problems of size. Management effectiveness can be increased by 20-30 percent. | |

| Role of Managers Under Different Styles of Management | Short summary of the role of managers under authoritarian and participative styles of management. Also covers decision making and the basic characteristics of each style. | |

| Motivation Summary | Reviews and summarises past work in Motivation. Provides a clear definition of 'motivation', of the factors which motivate and of what people are striving to achieve. | |

| Directing and Managing Change | How to plan ahead, find best strategies, decide and implement, agree targets and objectives, monitor and control progress, evaluate performance, carry out appraisal and target-setting interviews. Describes proved, practical and effective techniques. | |

| The Will to Work: What People Struggle to Achieve | Major review, analysis and report about motivation and motivating. Covers remuneration and job satisfaction as well as the factors which motivate. Develops a clear definition of 'motivation'. Lists what people are striving and struggling to achieve, and progress made, in corporations, communities, countries. | |

| Work and Pay | Major review and analysis of work and pay in relation to employer, employee and community. Provides the underlying knowledge and understanding for scientific determination and prediction of rates of pay, remuneration and differentials, of National Remuneration Scales and of the National Remuneration Pattern of pay and differentials. | |

| Work and Pay: Summary | Concise summary review of whole subject of work and pay, in clear language. Covers pay, incomes and differentials and the interests and requirements of owners and employers, of the individual and his family, and of the community. | |

| Exporting and Importing of Employment and Unemployment | Discusses exporting and importing of employment and unemployment, underlying principles, effect of trade, how to reduce unemployment, social costs of unemployment, community objectives, support for enterprises, socially irresponsible enterprise behaviour. | |

| Transfer Pricing and Taxation | One of the most controversial operations of multinationals, transfer pricing, is clearly described and defined. An easily-followed illustration shows how transfer pricing can be used by multinationals to maximise their profits by tax avoidance and by obtaining tax rebates. Also discussed is the effect of transfer pricing on the tax burden carried by other tax payers. | |

| Inflation, Balance of Payments and Currency Exchange Rates | Reviews the relationships, how inflation affects currency exchange rates and trade, the effect of changing interest rates on share prices and pensions. Discusses multinational operations such as transfer pricing, inflation's burdens and worldwide inequality. | |

| Social Responsibility, Profits and Social Accountability | Incidents, disasters and catastrophes are here put together as individual case studies and reviewed as a whole. We are facing a sequence of events which are increasing in frequency, severity and extent. There are sections about what can be done about this, on community aims and community leadership, on the world-wide struggle for social accountability. | |

| Social Responsibility and Accountability: Summary | Outlines basic causes of socially irresponsible behaviour and ways of solving the problem. Statement of aims. Public demonstrations and protests as essential survival mechanisms. Whistle-blowing. Worldwide struggle to achieve social accountability. | |

| Co-operatives and Co-operation: Causes of Failure, Guidelines for Success | Based on eight studies of co-operatives and mutual societies, the report's conclusions and recommendations cover fundamental and practical problems of co-ops and mutual societies, of members, of direction, of management and control. There are extensive sections on Style of Management, decision-taking, management motivation and performance, on General Management principles and their application in practice. | |

| Using Words to Communicate Effectively | Shows how to communicate more effectively, covering aspects of thinking, writing, speaking and listening as well as formal and informal communications. Consists of guidelines found useful by university students and practising middle and senior managers. | |

| Community and Public Ownership | This report objectively evaluates community ownership and reviews the reasons both for nationalising and for privatising. Performance, control and accountability of community-owned enterprises and industries are discussed. Points made are illustrated by a number of striking case-studies. | |

| Ownership and Limited Liability | Discusses different types of enterprises and the extent to which owners are responsible for repaying the debts of their enterprise. Also discussed are disadvantages, difficulties and abuses associated with the system of Limited Liability, and their implications for customers, suppliers and employees. | |

| Ownership and Deciding Policy: Companies, Shareholders, Directors and Community | A short statement which describes the system by which a company's majority shareholders decide policy and control the company. | |

| The Right to Strike | Discusses and defines the right to strike, the extent to which people can strike and what this implies. Also discussed are aspects of current problems such as part-time work and home working, Works Councils, uses and misuses of linking pay to a cost-of-living index, participation in decision-taking, upward redistribution of income and wealth. | |

|

Reorganising the National Health

Service: An Evaluation of the Griffiths Report |

1984 report which has become a classic study of the application and effect of General Management principles and of ignoring them. | |

RELEVANT SUBJECT INDEX PAGES

Other Subjects; Other Publications

The Site Overview page has links to all individual Subject Index Pages which between them list the works by Manfred Davidmann which are available on the Internet, with short descriptions and links for downloading.

To see the Site Overview page, click Overview

Copyright © Manfred Davidmann 1981, 1982, 1989, 1995, 2006

ISBN 0 85192 030 6 Second edition 1982, 1989

All rights reserved worldwide.

Updated 2021:

Links to 'BOOKS', 'Donations' and 'Privacy Notice' were added

Terms of Use

Privacy Notice